Which of the Following Cultures Was Not Studied in Detail in This Chapter Art 101

iii.ii The Elements of Culture

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish textile culture and nonmaterial culture.

- Listing and ascertain the several elements of civilization.

- Describe certain values that distinguish the United States from other nations.

Culture was divers earlier as the symbols, language, behavior, values, and artifacts that are function of whatever lodge. As this definition suggests, in that location are two bones components of culture: ideas and symbols on the one hand and artifacts (cloth objects) on the other. The outset type, called nonmaterial culture, includes the values, beliefs, symbols, and language that ascertain a social club. The second type, chosen material civilisation, includes all the gild's concrete objects, such equally its tools and technology, wear, eating utensils, and means of transportation. These elements of culture are discussed next.

Symbols

Every culture is filled with symbols, or things that stand for something else and that often evoke various reactions and emotions. Some symbols are actually types of nonverbal communication, while other symbols are in fact fabric objects. As the symbolic interactionist perspective discussed in Chapter 1 "Sociology and the Sociological Perspective" emphasizes, shared symbols make social interaction possible.

Allow'south look at nonverbal symbols first. A common i is shaking hands, which is washed in some societies but non in others. It unremarkably conveys friendship and is used as a sign of both greeting and deviation. Probably all societies have nonverbal symbols we call gestures, movements of the hands, arms, or other parts of the body that are meant to convey certain ideas or emotions. However, the same gesture can mean one matter in one society and something quite different in another society (Axtell, 1998). In the United States, for example, if we nod our caput upwards and downwardly, we mean yes, and if we milkshake it dorsum and forth, nosotros mean no. In Bulgaria, however, nodding means no, while shaking our head back and along means yes! In the United States, if we make an "O" by putting our pollex and forefinger together, we mean "OK," simply the same gesture in certain parts of Europe signifies an obscenity. "Thumbs up" in the U.s.a. ways "not bad" or "wonderful," merely in Australia information technology means the same thing as extending the middle finger in the United States. Sure parts of the Eye Due east and Asia would exist offended if they saw y'all using your left manus to swallow, because they utilise their left hand for bathroom hygiene.

The meaning of a gesture may differ from i club to another. This familiar gesture ways "OK" in the United States, but in certain parts of Europe information technology signifies an obscenity. An American using this gesture might very well be greeted with an aroused expect.

d Wang – ok – CC BY-NC-ND ii.0.

Some of our most important symbols are objects. Here the U.S. flag is a prime number instance. For most Americans, the flag is non just a piece of cloth with red and white stripes and white stars against a field of blueish. Instead, it is a symbol of liberty, democracy, and other American values and, accordingly, inspires pride and patriotism. During the Vietnam War, however, the flag became to many Americans a symbol of war and imperialism. Some burned the flag in protest, prompting angry attacks by bystanders and negative coverage by the news media.

Other objects have symbolic value for religious reasons. Iii of the most familiar religious symbols in many nations are the cross, the Star of David, and the crescent moon, which are widely understood to represent Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, respectively. Whereas many cultures attach no religious significance to these shapes, for many people across the earth they evoke very strong feelings of religious organized religion. Recognizing this, hate groups have often desecrated these symbols.

As these examples indicate, shared symbols, both nonverbal advice and tangible objects, are an important part of any culture only likewise tin can lead to misunderstandings and fifty-fifty hostility. These problems underscore the significance of symbols for social interaction and significant.

Language

Possibly our most of import set of symbols is language. In English language, the word chair means something we sit on. In Spanish, the discussion silla means the aforementioned thing. As long as nosotros agree how to interpret these words, a shared language and thus club are possible. By the aforementioned token, differences in languages can make it quite difficult to communicate. For example, imagine you are in a strange country where you do not know the language and the country's citizens practise not know yours. Worse notwithstanding, you forgot to bring your lexicon that translates their language into yours, and vice versa, and your iPhone battery has died. Y'all get lost. How will yous become help? What will you do? Is at that place any way to communicate your plight?

As this scenario suggests, language is crucial to advice and thus to any society's culture. Children acquire language from their culture but as they larn well-nigh shaking hands, almost gestures, and about the significance of the flag and other symbols. Humans have a capacity for language that no other creature species possesses. Our chapters for language in turn helps make our complex culture possible.

Language is a key symbol of any culture. Humans have a capacity for linguistic communication that no other beast species has, and children learn the language of their society merely every bit they acquire other aspects of their culture.

In the The states, some people consider a common language so important that they advocate making English the official language of certain cities or states or even the whole land and banning bilingual education in the public schools (Ray, 2007). Critics admit the importance of English only allege that this movement smacks of anti-immigrant prejudice and would help destroy ethnic subcultures. In 2009, voters in Nashville, Tennessee, rejected a proposal that would take made English the urban center's official language and required all metropolis workers to speak in English rather than their native language (R. Chocolate-brown, 2009).

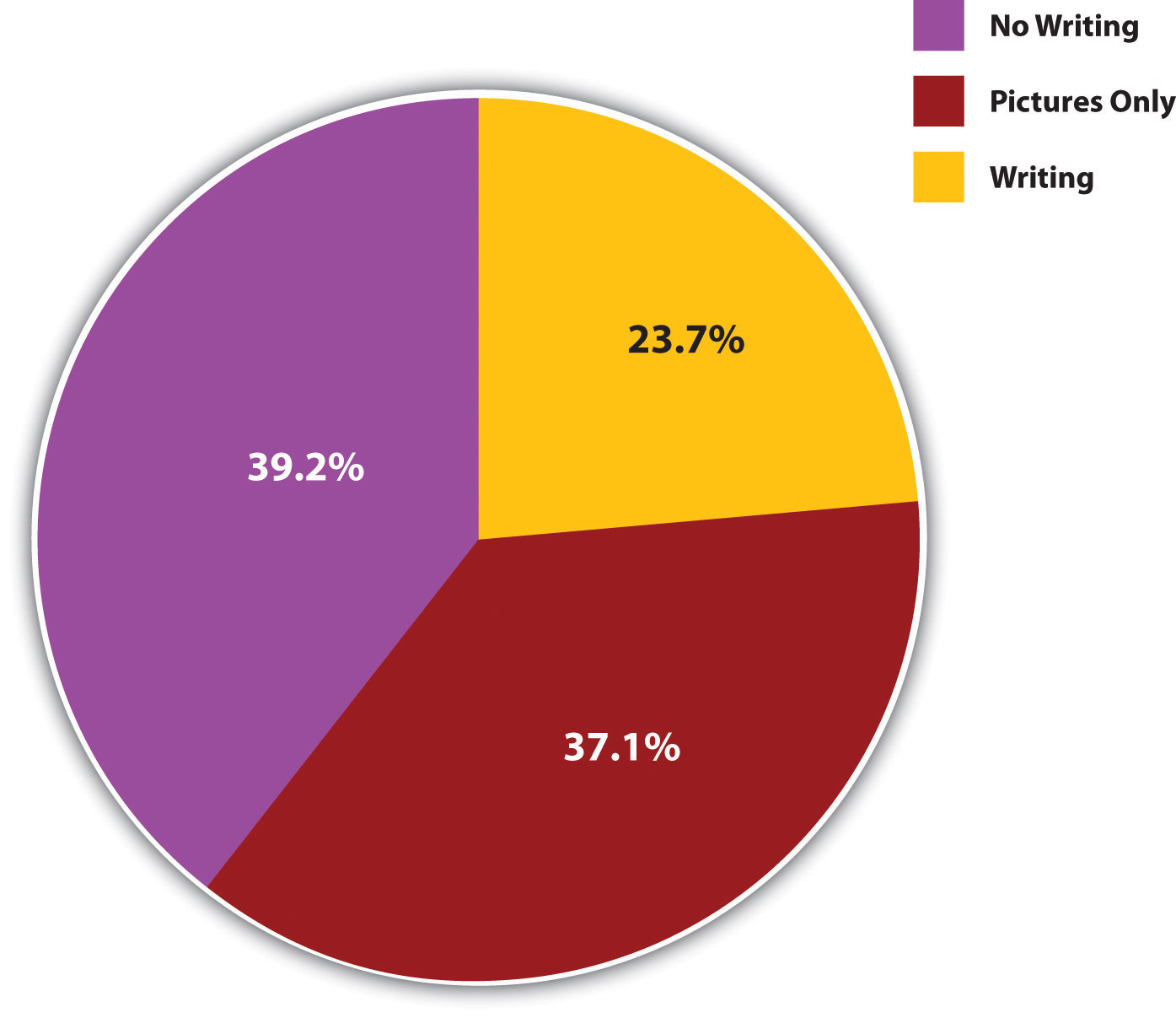

Linguistic communication, of course, tin can be spoken or written. One of the nearly important developments in the evolution of society was the creation of written language. Some of the preindustrial societies that anthropologists have studied have written linguistic communication, while others do not, and in the remaining societies the "written" linguistic communication consists mainly of pictures, non words. Figure 3.1 "The Presence of Written Language (Percentage of Societies)" illustrates this variation with data from 186 preindustrial societies called the Standard Cantankerous-Cultural Sample (SCCS), a famous data set compiled several decades ago by anthropologist George Murdock and colleagues from information that had been gathered on hundreds of preindustrial societies around the globe (Murdock & White, 1969). In Figure 3.1 "The Presence of Written Language (Percentage of Societies)", we run across that only about one-fourth of the SCCS societies take a written language, while about equal proportions have no language at all or only pictures.

Figure iii.1 The Presence of Written Linguistic communication (Percent of Societies)

Source: Data from Standard Cross-Cultural Sample.

To what extent does linguistic communication influence how we think and how nosotros perceive the social and physical worlds? The famous but controversial Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, named after 2 linguistic anthropologists, Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf, argues that people cannot hands understand concepts and objects unless their language contains words for these items (Whorf, 1956). Linguistic communication thus influences how we understand the world around us. For example, people in a country such as the U.s.a. that has many terms for different types of kisses (e.g. buss, peck, smack, smooch, and soul) are better able to appreciate these unlike types than people in a country such as Japan, which, as we saw earlier, only fairly recently developed the word kissu for kiss.

Another illustration of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is seen in sexist language, in which the use of male nouns and pronouns shapes how we think well-nigh the world (Miles, 2008). In older children'southward books, words like burnman and postal serviceman are common, along with pictures of men in these jobs, and critics say they ship a message to children that these are male jobs, non female jobs. If a teacher tells a 2d-grade class, "Every student should put his books under his desk-bound," the teacher obviously means students of both sexes but may be sending a subtle message that boys matter more girls. For these reasons, several guidebooks promote the use of nonsexist linguistic communication (Maggio, 1998). Tabular array iii.1 "Examples of Sexist Terms and Nonsexist Alternatives" provides examples of sexist language and nonsexist alternatives.

Tabular array 3.ane Examples of Sexist Terms and Nonsexist Alternatives

| Term | Alternative |

|---|---|

| Businessman | Businessperson, executive |

| Fireman | Firefighter |

| Chairman | Chair, chairperson |

| Policeman | Police officeholder |

| Mailman | Letter carrier, postal worker |

| Flesh | Humankind, people |

| Human-made | Artificial, synthetic |

| Waitress | Server |

| He (as generic pronoun) | He or she; he/she; s/he |

| "A professor should be devoted to his students" | "Professors should exist devoted to their students" |

The utilise of racist language as well illustrates the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis. An former saying goes, "Sticks and stones may intermission my basic, simply names will never hurt me." That may be truthful in theory only not in reality. Names tin hurt, especially names that are racial slurs, which African Americans growing up before the era of the ceremonious rights motility routinely heard. According to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, the apply of these words would have affected how whites perceived African Americans. More generally, the use of racist terms may reinforce racial prejudice and racial stereotypes.

Sociology Making a Difference

Overcoming Cultural and Indigenous Differences

People from many dissimilar racial and ethnic backgrounds live in large countries such as the United States. Because of cultural differences and diverse prejudices, information technology tin can be difficult for individuals from one background to collaborate with individuals from another groundwork. Fortunately, a line of research, grounded in contact theory and conducted by sociologists and social psychologists, suggests that interaction among individuals from dissimilar backgrounds can indeed assistance overcome tensions arising from their different cultures and any prejudices they may hold. This happens considering such contact helps disconfirm stereotypes that people may hold of those from unlike backgrounds (Dixon, 2006; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2005).

Recent studies of college students provide additional evidence that social contact tin can help overcome cultural differences and prejudices. Because many students are randomly assigned to their roommates when they enter higher, interracial roommates provide a "natural" experiment for studying the effects of social interaction on racial prejudice. Studies of such roommates observe that whites with black roommates report lowered racial prejudice and greater numbers of interracial friendships with other students (Laar, Levin, Sinclair, & Sidanius, 2005; Shook & Fazio, 2008).

It is not easy to overcome cultural differences and prejudices, and studies also find that interracial college roommates often take to confront many difficulties in overcoming the cultural differences and prejudices that existed before they started living together (Shook & Fazio, 2008). However the trunk of work supporting contact theory suggests that efforts that increase social interaction among people from dissimilar cultural and ethnic backgrounds in the long run will reduce racial and ethnic tensions.

Norms

Cultures differ widely in their norms, or standards and expectations for behaving. Nosotros already saw that the nature of drunken behavior depends on society's expectations of how people should behave when drunk. Norms of drunken behavior influence how we behave when nosotros drink likewise much.

Norms are often divided into two types, formal norms and informal norms. Formal norms, also called mores (MOOR-ayz) and laws, refer to the standards of behavior considered the most important in any lodge. Examples in the The states include traffic laws, criminal codes, and, in a college context, student behavior codes addressing such things every bit cheating and detest spoken language. Breezy norms, besides called folkways and community, refer to standards of behavior that are considered less of import but still influence how we conduct. Table manners are a common instance of informal norms, as are such everyday behaviors equally how we interact with a cashier and how nosotros ride in an elevator.

Many norms differ dramatically from one culture to the next. Some of the all-time testify for cultural variation in norms comes from the study of sexual behavior (Edgerton, 1976). Amid the Pokot of East Africa, for instance, women are expected to enjoy sex, while amongst the Gusii a few hundred miles abroad, women who enjoy sexual activity are considered deviant. In Inis Beag, a small isle off the coast of Republic of ireland, sex is considered embarrassing and even disgusting; men feel that intercourse drains their forcefulness, while women consider it a brunt. Even nudity is considered terrible, and people on Inis Beag keep their apparel on while they breast-stroke. The situation is quite unlike in Mangaia, a pocket-sized island in the South Pacific. Here sex is considered very enjoyable, and it is the major subject of songs and stories.

While many societies frown on homosexuality, others take it. Amidst the Azande of East Africa, for example, young warriors alive with each other and are not immune to marry. During this fourth dimension, they frequently accept sex with younger boys, and this homosexuality is approved by their culture. Amidst the Sambia of New Guinea, young males alive separately from females and engage in homosexual behavior for at to the lowest degree a decade. Information technology is felt that the boys would be less masculine if they continued to live with their mothers and that the semen of older males helps young boys go strong and fierce (Edgerton, 1976).

Although many societies disapprove of homosexuality, other societies take information technology. This difference illustrates the importance of culture for people's attitudes.

Other prove for cultural variation in norms comes from the study of how men and women are expected to behave in various societies. For example, many traditional societies are simple hunting-and-gathering societies. In most of these, men tend to hunt and women tend to gather. Many observers attribute this gender difference to at to the lowest degree two biological differences between the sexes. First, men tend to be bigger and stronger than women and are thus ameliorate suited for hunting. Second, women become pregnant and bear children and are less able to hunt. Yet a different pattern emerges in some hunting-and-gathering societies. Among a group of Australian aborigines chosen the Tiwi and a tribal club in the Philippines called the Agta, both sexes hunt. Afterwards condign pregnant, Agta women go on to hunt for most of their pregnancy and resume hunting afterward their child is born (Brettell & Sargent, 2009).

Some of the most interesting norms that differ past civilization govern how people stand apart when they talk with each other (Hall & Hall, 2007). In the United states, people who are not intimates commonly stand virtually three to four feet apart when they talk. If someone stands more closely to us, particularly if we are of northern European heritage, we feel uncomfortable. Yet people in other countries—especially Italy, France, Spain, and many of the nations of Latin America and the Heart East—would feel uncomfortable if they were standing three to iv feet apart. To them, this distance is too great and indicates that the people talking dislike each other. If a U.S. native of British or Scandinavian heritage were talking with a fellow member of one of these societies, they might well have trouble interacting, because at least 1 of them will be uncomfortable with the physical distance separating them.

Rituals

Different cultures likewise have different rituals, or established procedures and ceremonies that frequently mark transitions in the life course. As such, rituals both reflect and transmit a culture's norms and other elements from one generation to the next. Graduation ceremonies in colleges and universities are familiar examples of fourth dimension-honored rituals. In many societies, rituals help signify 1'southward gender identity. For example, girls around the world undergo diverse types of initiation ceremonies to mark their transition to machismo. Amongst the Bemba of Zambia, girls undergo a calendar month-long initiation anniversary called the chisungu, in which girls learn songs, dances, and secret terms that just women know (Maybury-Lewis, 1998). In some cultures, special ceremonies too marking a girl'southward first menstrual period. Such ceremonies are largely absent in the United States, where a girl's first catamenia is a private matter. But in other cultures the first period is a cause for celebration involving gifts, music, and food (Hathaway, 1997).

Boys have their ain initiation ceremonies, some of them involving circumcision. That said, the ways in which circumcisions are done and the ceremonies accompanying them differ widely. In the United States, boys who are circumcised normally undergo a quick procedure in the hospital. If their parents are observant Jews, circumcision will exist function of a religious anniversary, and a religious figure called a moyel will perform the circumcision. In contrast, circumcision among the Maasai of East Africa is used as a test of manhood. If a boy being circumcised shows signs of fear, he might well be ridiculed (Maybury-Lewis, 1998).

Are rituals more common in traditional societies than in industrial ones such equally the United States? Consider the Nacirema, studied by anthropologist Horace Miner more than 50 years ago (Miner, 1956). In this society, many rituals have been developed to deal with the civilisation's cardinal conventionalities that the human body is ugly and in danger of suffering many diseases. Reflecting this conventionalities, every household has at least one shrine in which various rituals are performed to cleanse the body. Frequently these shrines contain magic potions acquired from medicine men. The Nacirema are especially concerned about diseases of the oral cavity. Miner writes, "Were it non for the rituals of the mouth, they believe that their teeth would fall out, their gums drain, their jaws shrink, their friends desert them, and their lovers reject them" (p. 505). Many Nacirema engage in "mouth-rites" and see a "holy-oral cavity-man" in one case or twice yearly.

Spell Nacirema astern and yous will see that Miner was describing American culture. As his satire suggests, rituals are not express to preindustrial societies. Instead, they function in many kinds of societies to marker transitions in the life course and to transmit the norms of the culture from 1 generation to the side by side.

Changing Norms and Beliefs

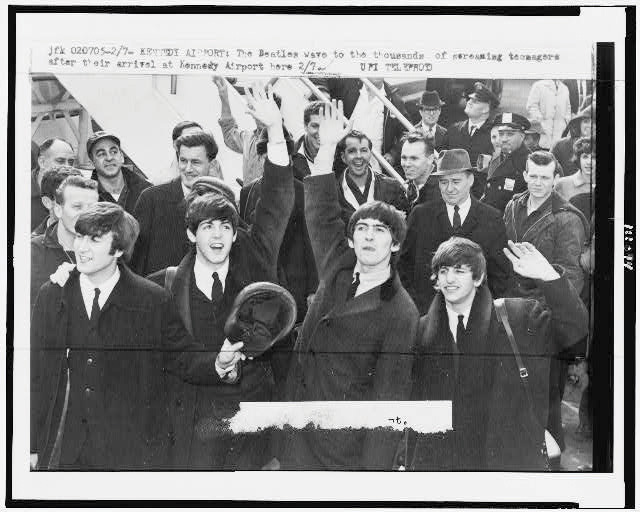

Our examples testify that unlike cultures have unlike norms, fifty-fifty if they share other types of practices and beliefs. It is also true that norms modify over fourth dimension inside a given culture. Ii obvious examples here are hairstyles and wearable styles. When the Beatles first became popular in the early 1960s, their hair barely covered their ears, but parents of teenagers back then were aghast at how they looked. If anything, clothing styles alter fifty-fifty more than ofttimes than hairstyles. Hemlines go up, hemlines go downwards. Lapels get wider, lapels get narrower. This color is in, that color is out. Hold on to your out-of-style clothes long enough, and eventually they may well finish up back in manner.

Some norms may change over fourth dimension within a given culture. In the early 1960s, the hair of the four members of the Beatles barely covered their ears, only many parents of U.S. teenagers were very critical of the length of their pilus.

A more than important topic on which norms have inverse is abortion and nativity control (Bullough & Bullough, 1977). Despite the controversy surrounding ballgame today, it was very mutual in the ancient world. Much subsequently, medieval theologians generally felt that ballgame was non murder if it occurred within the showtime several weeks after conception. This distinction was eliminated in 1869, when Pope Pius Nine alleged abortion at any fourth dimension to be murder. In the Us, ballgame was not illegal until 1828, when New York state banned it to protect women from unskilled abortionists, and most other states followed arrange by the end of the century. Nevertheless, the sheer number of unsafe, illegal abortions over the next several decades helped fuel a need for repeal of abortion laws that in plow helped lead to the Roe v. Wade Supreme Courtroom decision in 1973 that more often than not legalized abortion during the start 2 trimesters.

Contraception was also proficient in ancient times, but to exist opposed by early Christianity. Over the centuries, scientific discoveries of the nature of the reproductive process led to more effective means of contraception and to greater calls for its use, despite legal bans on the distribution of information about contraception. In the early on 1900s, Margaret Sanger, an American nurse, spearheaded the growing birth-control movement and helped open a birth-control clinic in Brooklyn in 1916. She and two other women were arrested within 10 days, and Sanger and i other defendant were sentenced to 30 days in jail. Efforts by Sanger and other activists helped to alter views on contraception over time, and finally, in 1965, the U.Southward. Supreme Court ruled in Griswold 5. Connecticut that contraception information could non be banned. As this brief summary illustrates, norms about contraception changed dramatically during the last century.

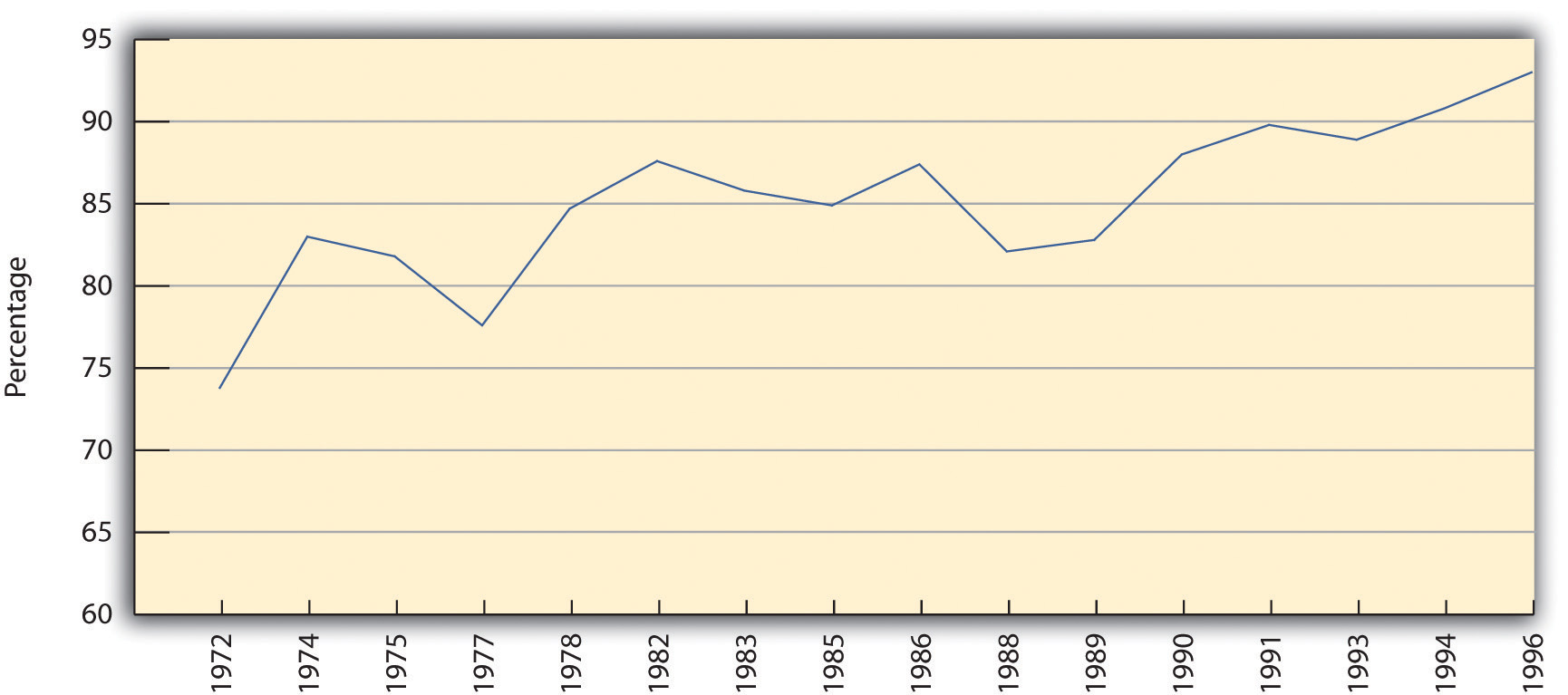

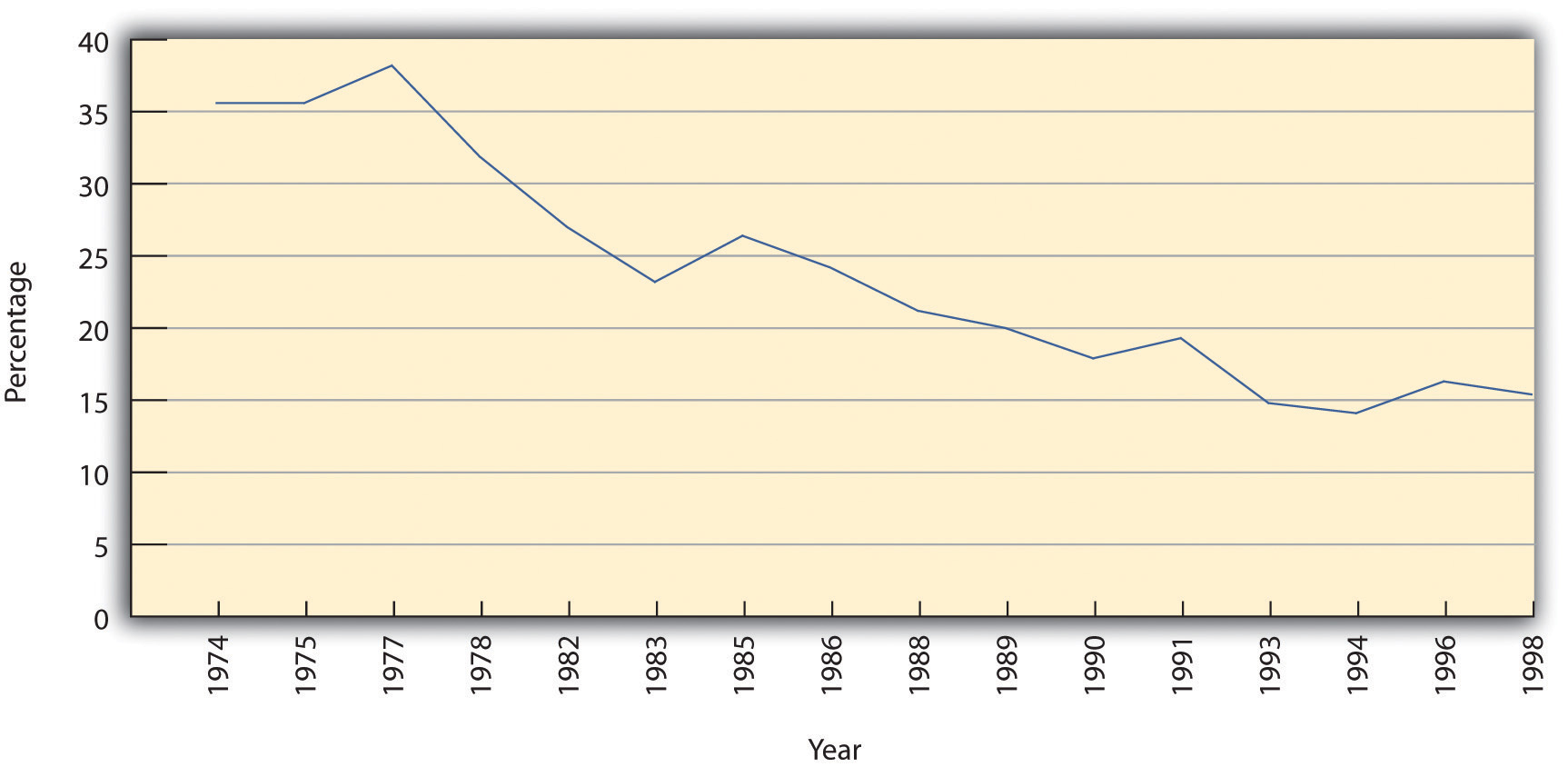

Other types of cultural beliefs also change over time (Figure 3.two "Percentage of People Who Say They Would Vote for a Qualified African American for President" and Effigy 3.three "Per centum of People Who Agree Women Should Take Care of Running Their Homes"). Since the 1960s, the U.Southward. public has changed its views about some of import racial and gender issues. Figure three.2 "Percentage of People Who Say They Would Vote for a Qualified African American for President", taken from several years of the Full general Social Survey (GSS), shows that the per centum of Americans who would vote for a qualified black person as president rose almost 20 points from the early 1970s to the middle of 1996, when the GSS stopped request the question. If beliefs about voting for an African American had non changed, Barack Obama would almost certainly non accept been elected in 2008. Figure 3.3 "Percent of People Who Agree Women Should Accept Care of Running Their Homes", also taken from several years of the GSS, shows that the per centum maxim that women should accept care of running their homes and leave running the land to men declined from almost 36% in the early 1970s to only about 15% in 1998, again, when the GSS stopped request the question. These two figures depict declining racial and gender prejudice in the Usa during the past quarter-century.

Effigy 3.2 Percentage of People Who Say They Would Vote for a Qualified African American for President

Source: Data from General Social Surveys, 1972–1996.

Figure iii.3 Percentage of People Who Agree Women Should Take Care of Running Their Homes

Source: Information from Full general Social Surveys, 1974–1998.

Values

Values are another of import chemical element of culture and involve judgments of what is expert or bad and desirable or undesirable. A culture's values shape its norms. In Japan, for instance, a primal value is group harmony. The Japanese place bang-up accent on harmonious social relationships and dislike interpersonal conflict. Individuals are fairly unassertive past American standards, lest they be perceived equally trying to force their volition on others (Schneider & Silverman, 2010). When interpersonal disputes do arise, Japanese practice their all-time to minimize disharmonize by trying to resolve the disputes amicably. Lawsuits are thus uncommon; in i example involving disease and death from a mercury-polluted river, some Japanese who dared to sue the company responsible for the mercury poisoning were considered bad citizens (Upham, 1976).

Individualism in the United states of america

American civilization promotes contest and an emphasis on winning in the sports and business worlds and in other spheres of life. Appropriately, lawsuits over frivolous reasons are mutual and even expected.

In the United States, of course, the situation is quite different. The American culture extols the rights of the individual and promotes competition in the business organization and sports worlds and in other areas of life. Lawsuits over the most frivolous of issues are quite common and even expected. Phrases like "Look out for number one!" abound. If the Japanese value harmony and grouping feeling, Americans value competition and individualism. Because the Japanese value harmony, their norms frown on self-assertion in interpersonal relationships and on lawsuits to correct perceived wrongs. Because Americans value and even thrive on contest, our norms promote assertion in relationships and certainly promote the utilize of the law to address all kinds of problems.

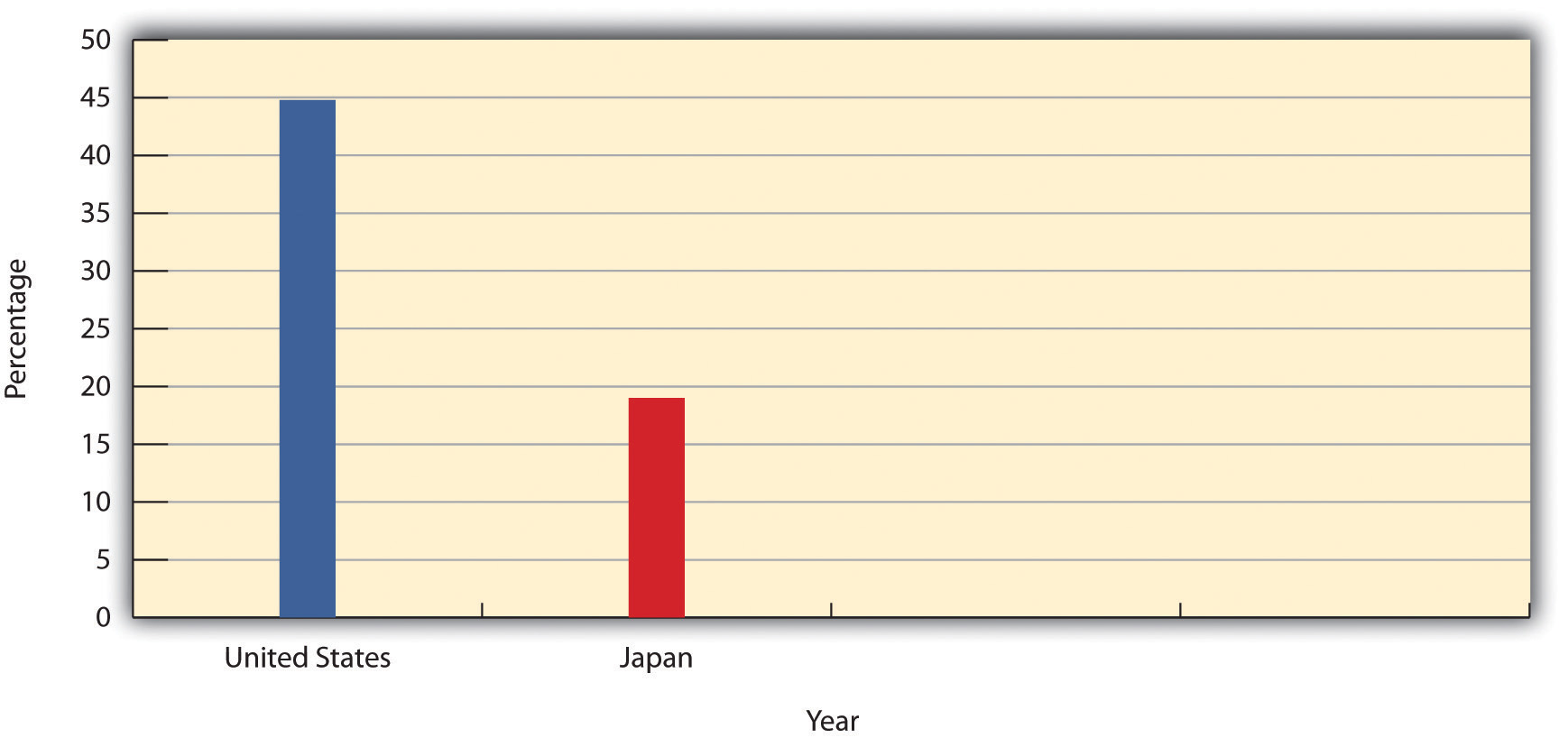

Effigy 3.4 "Percent of People Who Retrieve Competition Is Very Beneficial" illustrates this deviation between the 2 nations' cultures with data from the 2002 Globe Values Survey (WVS), which was administered to random samples of the adult populations of more 80 nations around the world. I question asked in these nations was, "On a scale of one ('competition is skillful; it stimulates people to work hard and develop new ideas') to ten ('competition is harmful; it brings out the worst in people'), please signal your views on contest." Figure 3.4 "Pct of People Who Call back Competition Is Very Beneficial" shows the percentages of Americans and Japanese who responded with a "one" or "2" to this question, indicating they recollect competition is very beneficial. Americans are nearly three times as likely as Japanese to favor competition.

Figure 3.four Per centum of People Who Think Contest Is Very Benign

Source: Information from World Values Survey, 2002.

The Japanese value system is a bit of an bibelot, because Japan is an industrial nation with very traditional influences. Its emphasis on group harmony and community is more usually thought of equally a value found in traditional societies, while the U.South. emphasis on individuality is more usually thought of as a value found in industrial cultures. Anthropologist David Maybury-Lewis (1998, p. 8) describes this difference every bit follows: "The heart of the divergence between the modern world and the traditional one is that in traditional societies people are a valuable resource and the interrelations between them are advisedly tended; in modern society things are the valuables and people are all too often treated equally disposable." In industrial societies, continues Maybury-Lewis, individualism and the rights of the individual are historic and any one person'south obligations to the larger community are weakened. Individual achievement becomes more important than values such as kindness, compassion, and generosity.

Other scholars accept a less bleak view of industrial lodge, where they say the spirit of customs still lives fifty-fifty as individualism is extolled (Bellah, Madsen, Sullivan, Swidler, & Tipton, 1985). In American society, these ii simultaneous values sometimes create tension. In Appalachia, for example, people view themselves as rugged individuals who want to control their own fate. At the same time, they have potent ties to families, relatives, and their neighbors. Thus their sense of independence conflicts with their need for dependence on others (Erikson, 1976).

The Work Ethic

Another important value in the American culture is the work ethic. By the 19th century, Americans had come up to view hard work non simply every bit something that had to be done but every bit something that was morally good to do (Gini, 2000). The commitment to the work ethic remains strong today: in the 2008 General Social Survey, 72% of respondents said they would go along to piece of work even if they got enough money to alive equally comfortably as they would similar for the remainder of their lives.

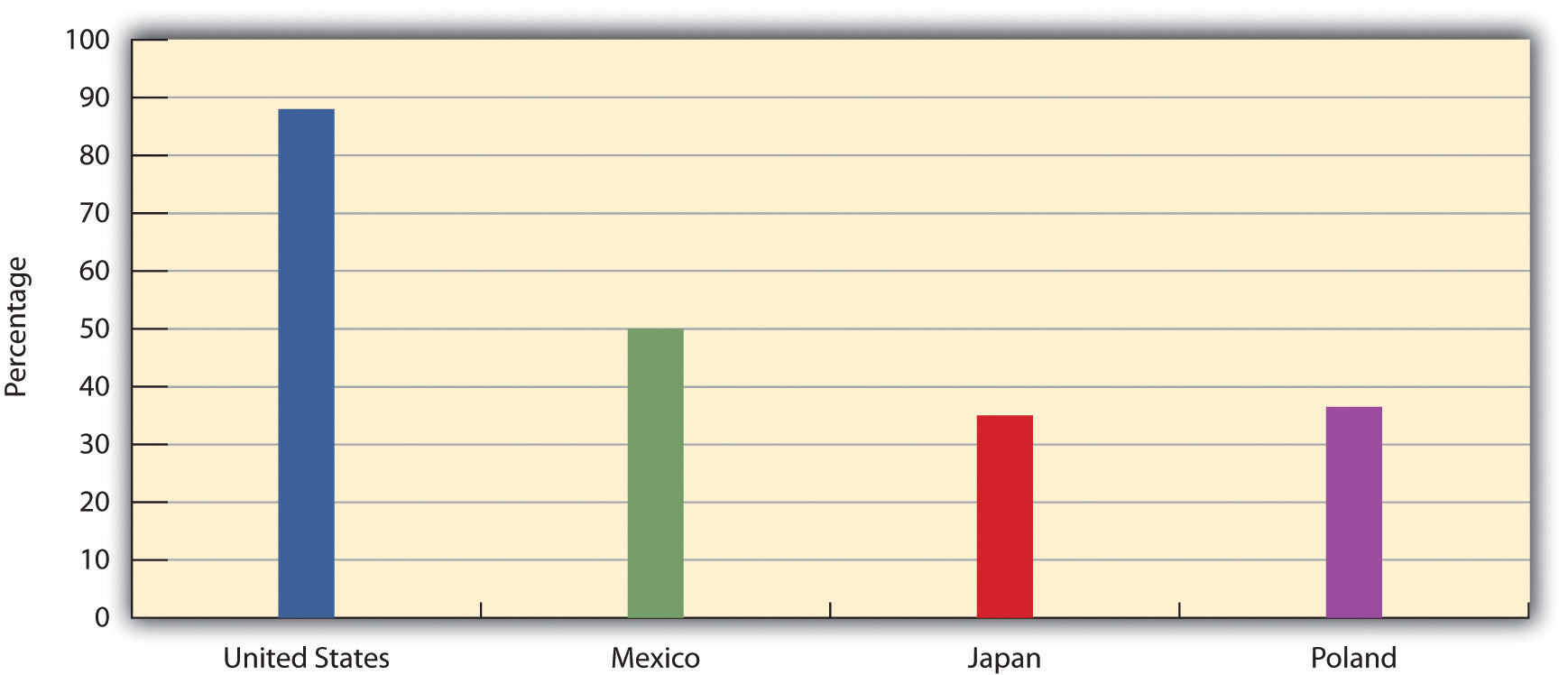

Cantankerous-cultural evidence supports the importance of the work ethic in the United States. Using earlier World Values Survey data, Effigy 3.5 "Percentage of People Who Have a Bully Deal of Pride in Their Work" presents the percentage of people in United states and three other nations from different parts of the earth—Mexico, Poland, and Japan—who have "a great bargain of pride" in their work. More than 85% of Americans feel this style, compared to much lower proportions of people in the other three nations.

Figure iii.5 Percentage of People Who Take a Bang-up Bargain of Pride in Their Work

Source: Data from World Values Survey, 1993.

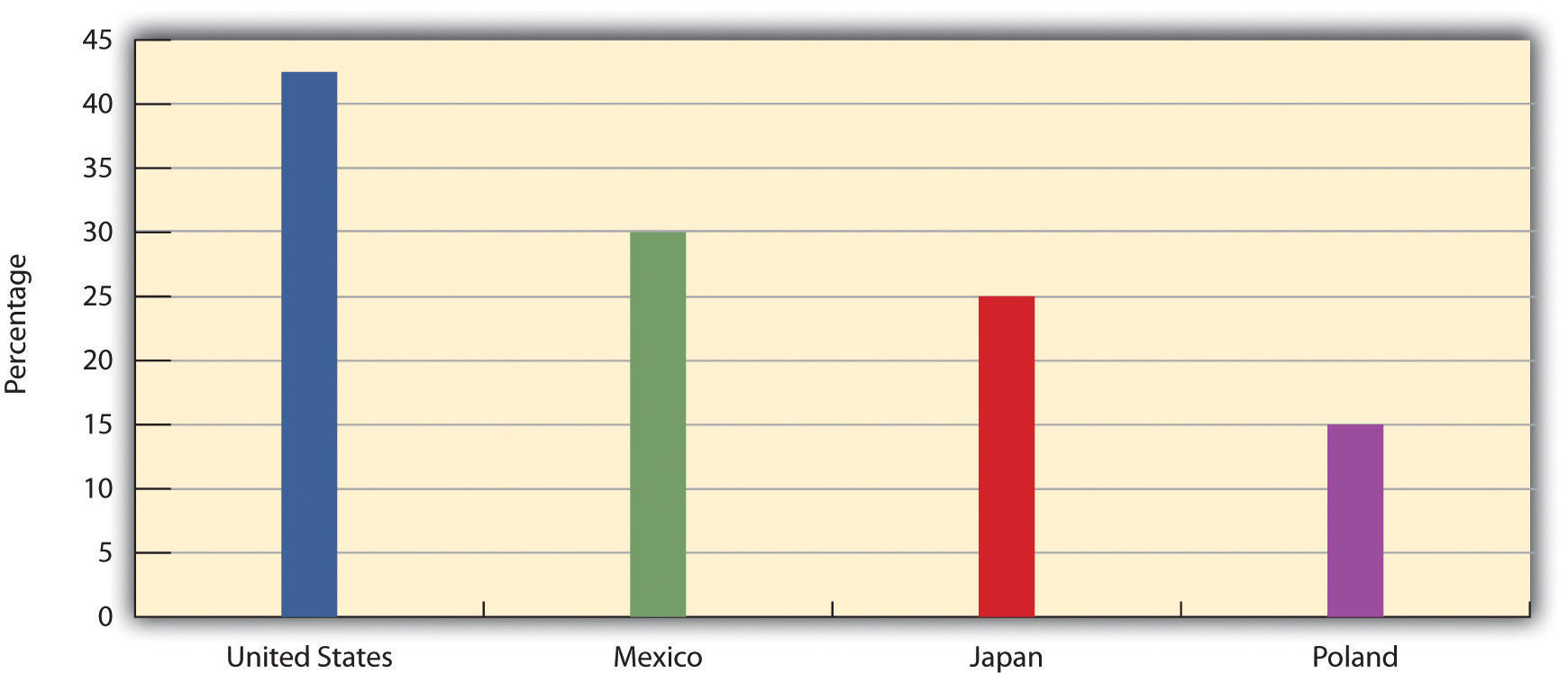

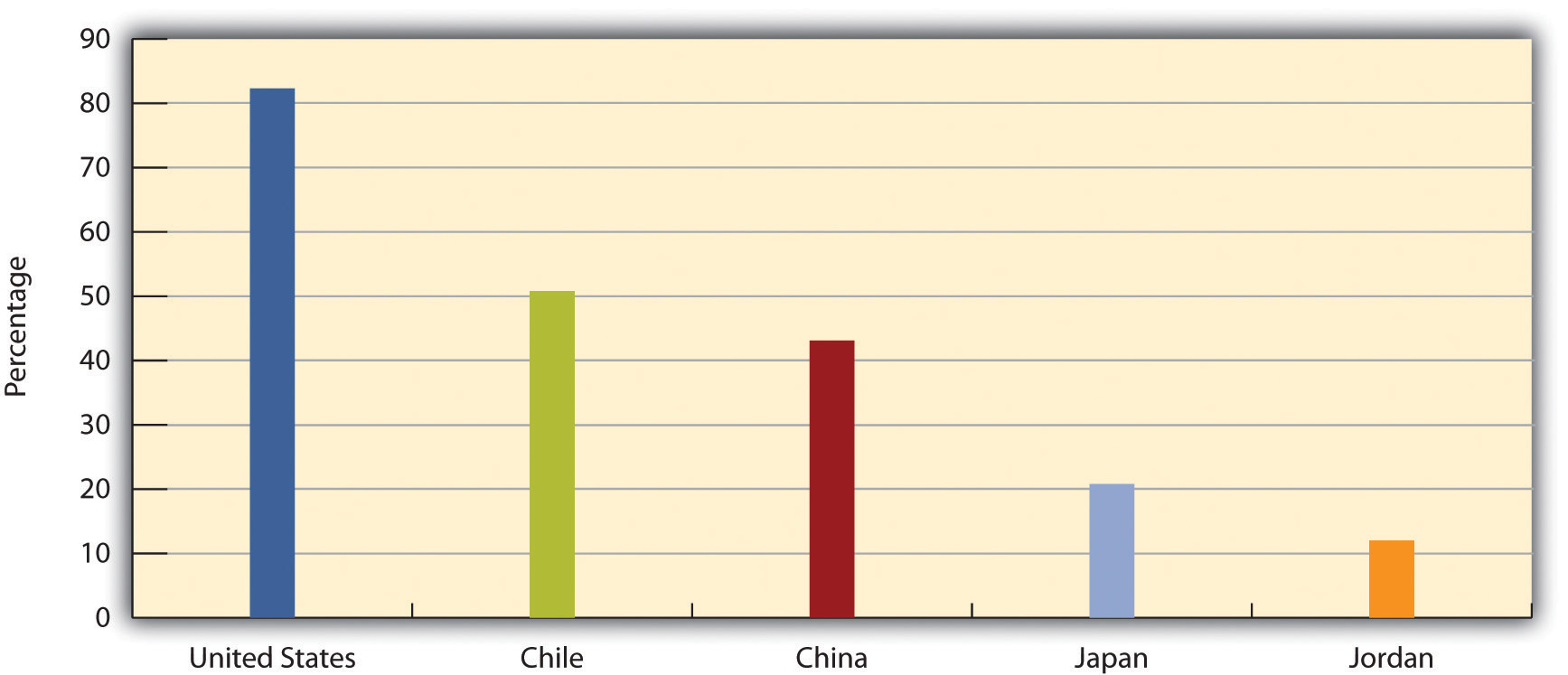

Closely related to the piece of work ethic is the belief that if people work hard enough, they volition be successful. Here again the American culture is especially thought to promote the idea that people can pull themselves upwards by their "bootstraps" if they piece of work difficult enough. The WVS asked whether success results from hard work or from luck and connections. Figure iii.six "Percent of People Who Think Hard Piece of work Brings Success" presents the proportions of people in the four nations but examined who nigh strongly thought that hard work brings success. In one case once again we run into evidence of an important aspect of the American culture, as U.Due south. residents were especially probable to think that difficult work brings success.

Figure 3.6 Percentage of People Who Recollect Hard Piece of work Brings Success

Source: Data from World Values Survey, 1997.

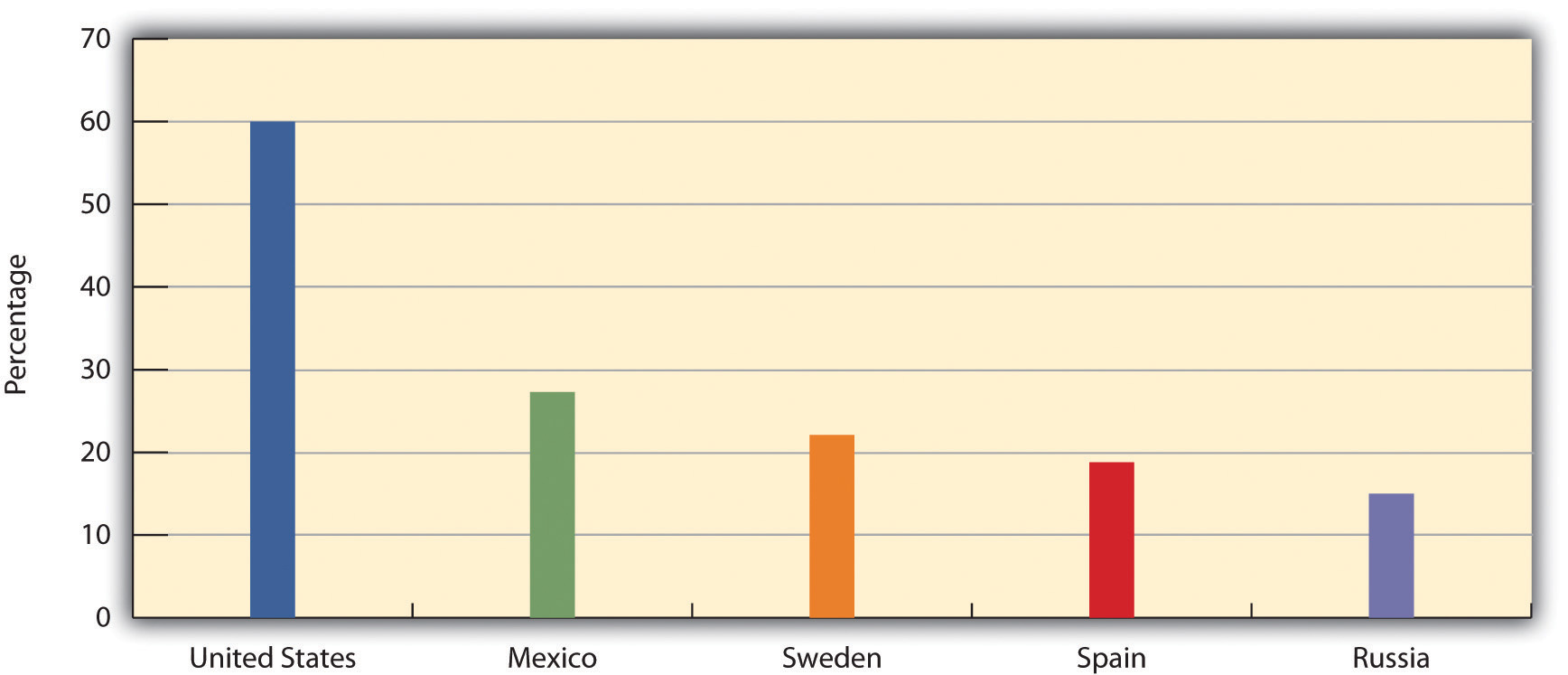

If Americans believe hard piece of work brings success, then they should be more than likely than people in nearly other nations to believe that poverty stems from not working difficult plenty. True or fake, this belief is an example of the blaming-the-victim ideology introduced in Chapter 1 "Sociology and the Sociological Perspective". Figure 3.7 "Per centum of People Who Attribute Poverty to Laziness and Lack of Willpower" presents WVS percentages of respondents who said the almost important reason people are poor is "laziness and lack of willpower." Every bit expected, Americans are much more than likely to attribute poverty to not working hard enough.

Figure 3.seven Pct of People Who Aspect Poverty to Laziness and Lack of Willpower

Source: Information from Earth Values Survey, 1997.

Nosotros could discuss many other values, merely an important one concerns how much a order values women's employment outside the home. The WVS asked respondents whether they agree that "when jobs are scarce men should have more right to a job than women." Figure 3.viii "Percentage of People Who Disagree That Men Take More Right to a Job Than Women When Jobs Are Deficient" shows that U.S. residents are more than likely than those in nations with more traditional views of women to disagree with this statement.

Figure iii.8 Percentage of People Who Disagree That Men Have More Right to a Job Than Women When Jobs Are Scarce

Source: Data from Globe Values Survey, 2002.

Artifacts

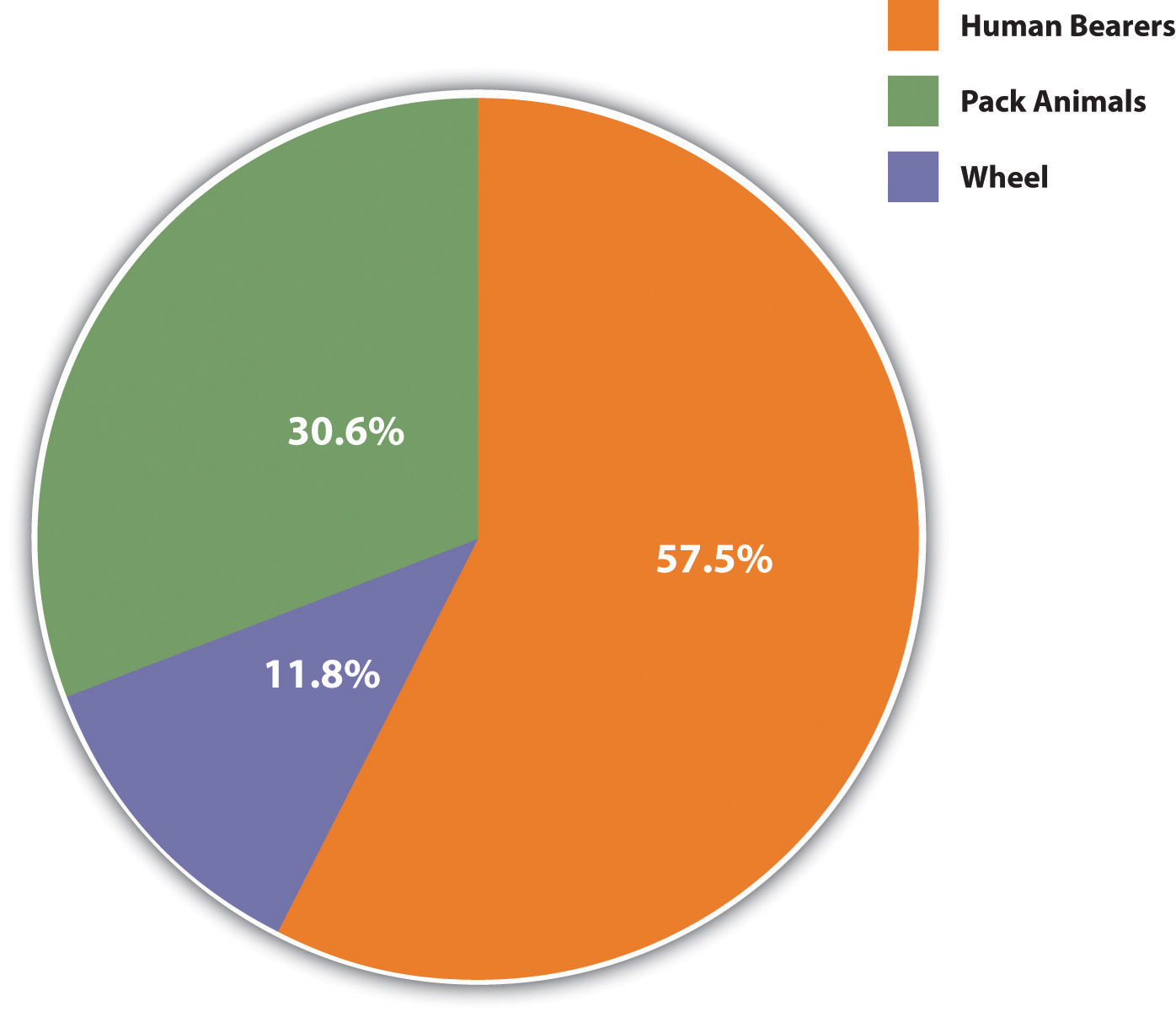

The last element of culture is the artifacts, or material objects, that constitute a society'due south material civilisation. In the most simple societies, artifacts are largely express to a few tools, the huts people live in, and the clothing they wearable. One of the most of import inventions in the development of gild was the bike. Effigy 3.9 "Principal Means of Moving Heavy Loads" shows that very few of the societies in the SCCS utilize wheels to move heavy loads over land, while the majority apply human being ability and about one-third use pack animals.

Figure 3.9 Master Means of Moving Heavy Loads

Source: Data from Standard Cross-Cultural Sample.

Although the wheel was a great invention, artifacts are much more numerous and complex in industrial societies. Because of technological advances during the past two decades, many such societies today may exist said to have a wireless culture, as smartphones, netbooks and laptops, and GPS devices at present dominate and then much of modern life. The artifacts associated with this culture were unknown a generation ago. Technological development created these artifacts and new language to describe them and the functions they perform. Today's wireless artifacts in plough help reinforce our ain commitment to wireless technology as a style of life, if only considering children are at present growing upwards with them, often even before they can read and write.

The iPhone is simply i of the many notable cultural artifacts in today's wireless world. Technological development created these artifacts and new language to describe them and their functions—for example, "There'due south an app for that!"

Philip Brooks – iPhone – CC Past-NC-ND 2.0.

Sometimes people in one lodge may find information technology difficult to sympathize the artifacts that are an of import part of another social club's civilization. If a member of a tribal society who had never seen a prison cell phone, or who had never even used batteries or electricity, were somehow to visit the United States, she or he would obviously take no idea of what a prison cell telephone was or of its importance in most everything we practice these days. Conversely, if we were to visit that person's guild, we might not capeesh the importance of some of its artifacts.

In this regard, consider once again India's cows, discussed in the news commodity that began this chapter. Every bit the article mentioned, people from Republic of india consider cows holy, and they let cows roam the streets of many cities. In a nation where hunger is so rampant, such cow worship is difficult to understand, at to the lowest degree to Americans, because a ready source of meat is being ignored.

Anthropologist Marvin Harris (1974) advanced a practical explanation for India'due south cow worship. Millions of Indians are peasants who rely on their farms for their food and thus their existence. Oxen and water buffalo, not tractors, are the way they plow their fields. If their ox falls sick or dies, farmers may lose their farms. Because, equally Harris observes, oxen are made by cows, it thus becomes essential to preserve cows at all costs. In Bharat, cows also act equally an essential source of fertilizer, to the tune of 700 million tons of manure annually, about half of which is used for fertilizer and the other half of which is used every bit fuel for cooking. Cow manure is also mixed with h2o and used as flooring textile over clay floors in Indian households. For all of these reasons, cow worship is non so puzzling after all, because information technology helps preserve animals that are very important for Bharat's economy and other aspects of its way of life.

According to anthropologist Marvin Harris, cows are worshipped in Republic of india because they are such an important office of India'south agricultural economic system.

If Indians exalt cows, many Jews and Muslims feel the opposite most pigs: they refuse to eat any product made from pigs and then obey an injunction from the Old Testament of the Bible and from the Koran. Harris thinks this injunction existed because pig farming in aboriginal times would accept threatened the environmental of the Middle Due east. Sheep and cattle eat primarily grass, while pigs eat foods that people eat, such every bit basics, fruits, and especially grains. In some other problem, pigs do non provide milk and are much more difficult to herd than sheep or cattle. Next, pigs do non thrive well in the hot, dry climate in which the people of the Onetime Testament and Koran lived. Finally, sheep and cattle were a source of food dorsum so because beyond their ain meat they provided milk, cheese, and manure, and cattle were also used for plowing. In dissimilarity, pigs would take provided only their ain meat. Because sheep and cattle were more "versatile" in all of these ways, and because of the other issues pigs would have posed, information technology made sense for the eating of pork to be prohibited.

In dissimilarity to Jews and Muslims, at least ane guild, the Maring of the mountains of New Guinea, is characterized by "pig love." Here pigs are held in the highest regard. The Maring sleep next to pigs, give them names and talk to them, feed them table scraps, and one time or twice every generation have a mass pig sacrifice that is intended to ensure the time to come wellness and welfare of Maring guild. Harris explains their love of pigs by noting that their climate is ideally suited to raising pigs, which are an of import source of meat for the Maring. Because besides many pigs would overrun the Maring, their periodic pig sacrifices assist keep the grunter population to manageable levels. Pig love thus makes as much sense for the Maring as pig hatred did for people in the time of the Sometime Attestation and the Koran.

Primal Takeaways

- The major elements of culture are symbols, linguistic communication, norms, values, and artifacts.

- Language makes effective social interaction possible and influences how people conceive of concepts and objects.

- Major values that distinguish the United states include individualism, competition, and a delivery to the work ethic.

For Your Review

- How and why does the development of language illustrate the importance of civilisation and provide bear witness for the sociological perspective?

- Some people say the The states is as well individualistic and competitive, while other people say these values are part of what makes America great. What do y'all recall? Why?

References

Axtell, R. E. (1998). Gestures: The practice's and taboos of body language around the world. New York, NY: Wiley.

Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W. Yard., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. Thousand. (1985). Habits of the eye: Individualism and commitment in American life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Brettell, C. B., & Sargent, C. F. (Eds.). (2009). Gender in cross-cultural perspective (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Chocolate-brown, R. (2009, Jan 24). Nashville voters reject a proposal for English-just. The New York Times, p. A12.

Bullough, 5. L., & Bullough, B. (1977). Sin, sickness, and sanity: A history of sexual attitudes. New York, NY: New American Library.

Dixon, J. C. (2006). The ties that demark and those that don't: Toward reconciling grouping threat and contact theories of prejudice. Social Forces, 84, 2179–2204.

Edgerton, R. (1976). Deviance: A cross-cultural perspective. Menlo Park, CA: Cummings.

Erikson, K. T. (1976). Everything in its path: Devastation of community in the Buffalo Creek inundation. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Gini, A. (2000). My task, my self: Work and the creation of the modern individual. New York, NY: Routledge.

Hall, E. T., & Hall, G. R. (2007). The sounds of silence. In J. M. Henslin (Ed.), Downwardly to earth folklore: Introductory readings (pp. 109–117). New York, NY: Complimentary Printing.

Harris, M. (1974). Cows, pigs, wars, and witches: The riddles of culture. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Hathaway, N. (1997). Menstruum and menopause: Blood rites. In L. M. Salinger (Ed.), Deviant behavior 97/98 (pp. 12–15). Guilford, CT: Dushkin.

Laar, C. 5., Levin, S., Sinclair, S., & Sidanius, J. (2005). The result of university roommate contact on ethnic attitudes and behavior. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 41, 329–345.

Maggio, R. (1998). The dictionary of bias-free usage: A guide to nondiscriminatory linguistic communication. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press.

Maybury-Lewis, D. (1998). Tribal wisdom. In G. Finsterbusch (Ed.), Sociology 98/99 (pp. eight–12). Guilford, CT: Dushkin/McGraw-Hill.

Miles, S. (2008). Language and sexism. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Miner, H. (1956). Torso ritual among the Nacirema. American Anthropologist, 58, 503–507.

Murdock, M. P., & White, D. R. (1969). Standard cross-cultural sample. Ethnology, 8, 329–369.

Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2005). Allport's intergroup contact hypothesis: Its history and influence. In J. F. Dovidio, P. Due south. Glick, & 50. A. Rudman (Eds.), On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after Allport (pp. 262–277). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Ray, S. (2007). Politics over official language in the United States. International Studies, 44, 235–252.

Schneider, L., & Silverman, A. (2010). Global sociology: Introducing v contemporary societies (5th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Colina.

Shook, North. J., & Fazio, R. H. (2008). Interracial roommate relationships: An experimental test of the contact hypothesis. Psychological Science, 19, 717–723.

Shook, Due north. J., & Fazio, R. H. (2008). Roommate relationships: A comparing of interracial and same-race living situations. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 11, 425–437.

Upham, F. K. (1976). Litigation and moral consciousness in Japan: An interpretive analysis of four Japanese pollution suits. Law and Society Review, 10, 579–619.

Whorf, B. (1956). Language, thought and reality. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Source: https://open.lib.umn.edu/sociology/chapter/3-2-the-elements-of-culture/

0 Response to "Which of the Following Cultures Was Not Studied in Detail in This Chapter Art 101"

Post a Comment