Black and White Pictures of People Scratch Art Woman

How blackness women were whitewashed by art

Where are all the cute, powerful, black-skinned females from mythology and history? They were erased past Western art, argues Sophia Smith Galer.

C

Clash of the Titans was one of the most popular films of 1981. Its glittering retinue of Hollywood stars told the story of Perseus, the demigod from Greek mythology who kills a sea monster and saves the beautiful princess Andromeda from being said monster'south lunch. Such was the film's popularity that information technology was remade in 2010; the picture show managed a rather disparaging 26% on the Rotten Tomatoes site. How many of those rating the motion picture had a classical educational activity is unclear, merely mayhap information technology would have performed ameliorate had its producers done their research. Every bit according to British art historian Elizabeth McGrath's 1992 article The Black Andromeda, Andromeda was, indeed, originally depicted as a black princess from Ethiopia.

More than similar this:

– Eight odd details hidden in masterpieces

– The rare blue the Maya invented

– Striking images of black struggle

Anyone who watched either of the two Clash of the Titans films volition know that Judi Bowker and Alexa Devalos are both white women, and anyone who has seen Andromeda in a painting – perhaps Titian's or Poynter'southward – will believe she is white likewise. Only McGrath'south article was definitive in addressing three things: that all the Greek mythographers placed Andromeda as a princess of Ethiopia, that Ovid specifically refers to her nighttime skin and that artists throughout Western art history frequently omitted to describe her blackness because Andromeda was supposed to be beautiful, and blackness and beauty – for many of them – was dichotomous. At that place is no doubt about Andromena'due south race, according to Professor McGrath.

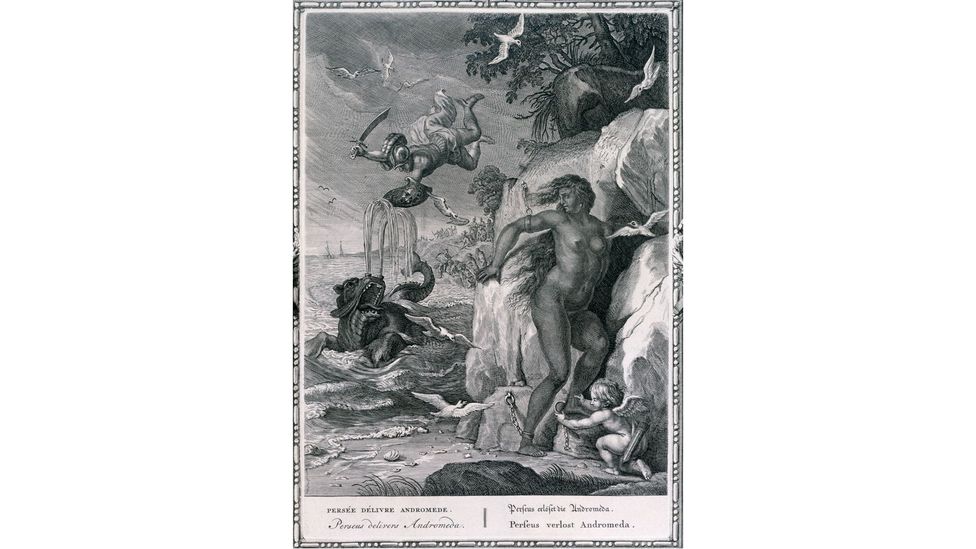

In Perseus Liberating Andromeda by Piero di Cosimo the princess is depicted as white (Credit: Getty Images)

Yet Renaissance art repeatedly depicts Andromeda equally white. In Piero di Cosimo's Perseus Freeing Andromeda from the 1510s she is actually whiter than all the figures around her, including a black musician and her parents, who are considerably darker and in exotic costume. Nosotros do know that in that location was active debate nigh her skin colour, a debate that would certainly seem racist to modern optics. McGrath references Francisco Pacheco, a Spanish artist and writer, who asks in 1 passage of his volume Arte de la Pintura why Andromeda is so oftentimes painted as white-skinned when several of the sources say she is black.

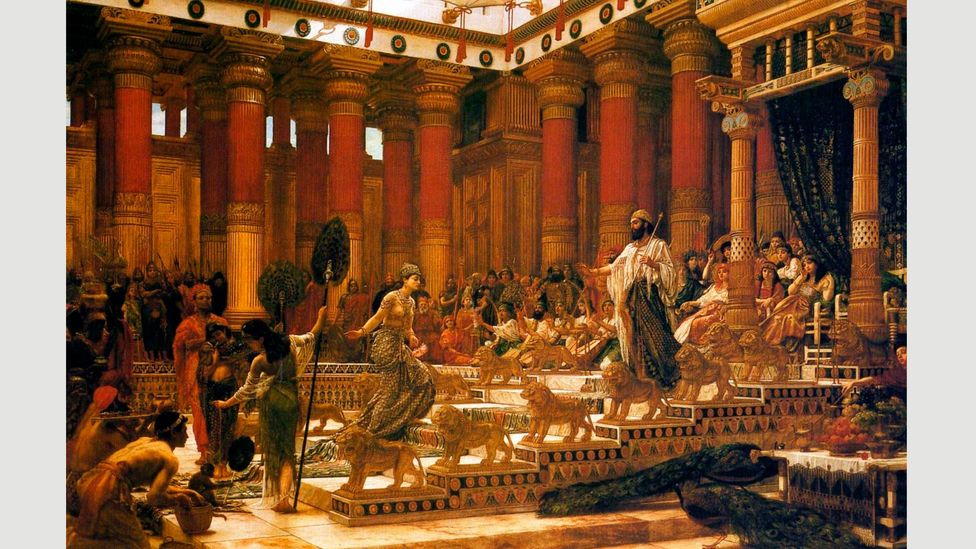

Edward Poynter's 1890 painting, the Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon, is another example of whitewashing (Credit: Alamy)

"He obviously got a terrible shock that Ovid could be talking about a woman as beautiful but black," McGrath tells BBC Culture, almost three decades later on the publication of her commodity. Books such as Pacheco'southward were used equally reference guides for painters on how to paint who and what – so it'due south like shooting fish in a barrel to run into how his views could take spread. Black Andromedas were few and far betwixt – and images similar Bernard Picart's print of Perseus (1731) and Andromeda past Abraham van Diepenbeeck (1655) appear to show a adult female with stereotypical white features and hair, but with night peel.

Princess Andromeda is portrayed with stereotypically white features and hair in Picart's 18th-Century engraving (Credit: Getty Images)

Andromeda is not the only black effigy in art that this has happened to, far from it. In fact, the whitewashing of Andromeda was prefigured in Renaissance Europe by Christianity.

Michael Ohajuru, an fine art historian who leads tours around London'southward galleries examining the representations of black people in art came to study Renaissance art history through his fascination with the blackness magus. This was 1 of the three kings, or magi, depicted in the nativity'south Adoration of the Magi scenes – typically the giver of myrrh. Ohajuru was surprised at the positivity of this figure that contrasted with history's many depictions of black people in servile roles. "The black king was used equally a positive figure," he says. Symbolising a young African continent that had come to join Europe and Asia in Christianity, "he was used equally an example of bringing the world together in the terminate times." Ohajuru searched for the black king's supposed origins and institute them in the Travels of Sir John Mandeville, a 14th Century text, which says that the black magus was from Saba, a kingdom in Ethiopia.

In the 1648 painting Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba by Claude Lorrain, the figure of the Ethiopian queen is white-skinned (Credit: Getty Images)

So Ohajuru was shocked to observe that many paintings of the Quondam Attestation'south visitor to King Solomon, the Queen of Sheba – another discussion for Saba – depicted her as a white adult female. He references Claude Lorrain'due south Seaport with the Embarkation of the Queen of Sheba, hanging in London's National Gallery. "She'due south shown in detail at the edge of the painting, but she's white. But the Queen of Sheba I knew came from Saba that was in Ethiopia, and the black king was from Saba. And then the Queen of Sheba had to be black in my mind."

All it takes is a few minutes of searching 'Queen of Sheba painting' on Google Images to meet a litany of reclining, exoticised white women glancing languorously either at the viewer or King Solomon. There were once some depictions of the Queen of Sheba as dark-skinned, but the Renaissance saw her whitewashing and sexualisation on a yard scale. For Ohajuru information technology jars with earlier depictions of her, such as that seen at the altarpiece of Klosterneuburg in Austria, which portrays her visiting the king adjacent to an image of the Adoration of the Magi. "She was used as a prefiguration, a foreteller, a prophesiser, that a male monarch would visit the baby Jesus, but as a queen visited Solomon." By the 18th Century she is no longer a queen meeting a king to take a healthy debate – she is an idolatrous seductress.

The 12th-Century altarpiece by Nicolas de Verdun depicts a black Queen of Sheba bringing gifts to King Solomon (Credit: Getty Images)

But those who depicted the Queen of Sheba – or indeed Andromeda – had a handy excuse. Ethiopia, for both the writers of the classics and students of the Bible, could mean very different things. As an Standard arabic speaker I've always understood that the Queen of Sheba was called Queen Belqis and came from Republic of yemen. The etymology of Federal democratic republic of ethiopia comes from the Ancient Greek for 'scorched faces'. To them, it was a byword for anyone from hotter, farther climes than their small-scale known world. "It'southward quite unstable," McGrath says. "It could exist anywhere in Africa, even India, these vague places, sunburnt places at either end of the Earth. Ethiopia can almost exist like a magic land where strange things happen.

"When they think, 'Well, Ethiopia tin can't really mean black people, Andromeda tin can't actually be black', they then discover all sorts of reasons to say that Ethiopia means something elsewhere. It means somewhere in the East. And they can hands indicate to the fact that there's a vagueness around the place of Ethiopia."

The translation of the Bible from which Renaissance artists would have been working had also gone through several iterations since its cosmos. McGrath writes in The Blackness Andromeda near how, in the original Hebrew so Greek, the Queen of Sheba declares in the Song of Solomon in the Old Attestation; "I am black and beautiful." By the time this makes information technology into the 405 AD translation into Latin Vulgate, 'and' becomes 'but'; "I am black but beautiful." In England, the 1611 publication of the King James Bible inverse it even further: "I am black but comely." The racist attitudes that diminished and hypersexualised black women are obvious. Maybe it's this phrase, rather than any painting, that has been the about subversive of them all.

Black is beautiful

Without the wisdom of the Queen of Sheba or the dazzler of Andromeda, images of black dazzler in fine art are rare; there are, of course, plenty of sketches and paintings of blackness people, but from the 18th Century onwards they largely focus on studies of fieldworkers, servants and slaves. At that place is the odd bibelot though – and these anomalies have us dorsum to kingdom of the netherlands, where the blackness magus every bit a symbol flourished.

In addition Elizabeth McGrath sees 17th-Century Antwerp as fairly open-minded. Inspired past Psalm 67, where Federal democratic republic of ethiopia 'volition stretch forth its hands to God' with its Gentiles, was some unusual artwork. According to the Old Testament, Moses married a 'Cushite', an Ethiopian, and in Jacob Jordaens' depiction of Moses and his Ethiopian wife in 1650, the couple "face, indeed might even seem to challenge, the very prejudices of the spectator." God actually gives Moses' sister Miriam leprosy for a week to punish her for speaking 'confronting' Moses' selection of bride; information technology'southward an unlikely iconographic depiction of anti-racism.

The Four Rivers of Paradise past Rubens is unusual in its delineation of a powerful black female figure (Credit: Getty Images)

Peter Paul Rubens, the artist credited with 'making big beautiful', likewise made black cute in The Four Rivers in the 1610. The four rivers are personified, and anybody is, well, pretty Rubenesque, with rippling muscles and heaving bosoms. In the middle sits the Nile, the only figure to stare directly at the viewer. Her nudity is tantalisingly hidden, her skin is nighttime and she is by far the well-nigh bejewelled figure in the piece. Aye, she's exoticised, but there's a ability to her – and she'southward equal to the white women in the image. "At that place was an involvement in painting blackness people in Antwerp, partly because of the conversion of black people, partly because people actually saw black people in the streets," says McGrath.

These practice, even so, remain anomalies in Western art history, McGrath explains. "I reason that the blackness king goes out of favour is that people – religious artists and theologians – are not so interested in the old religious symbolism of Ethiopia and the Gentiles." And then figures whose Ethiopian-ness was part of their entreatment were simply seen as unimportant.

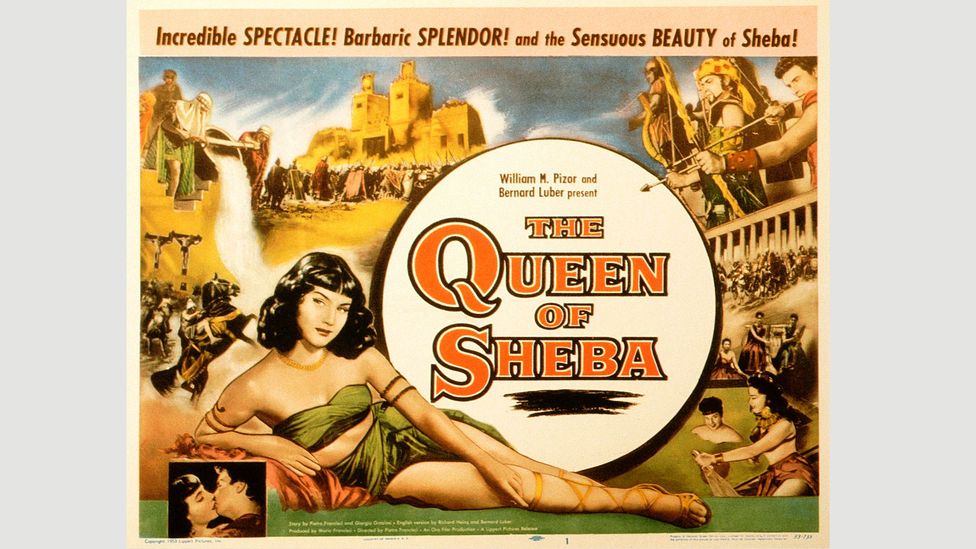

A U.s. affiche for the 1952 pic The Queen of Sheba (Credit: Alamy)

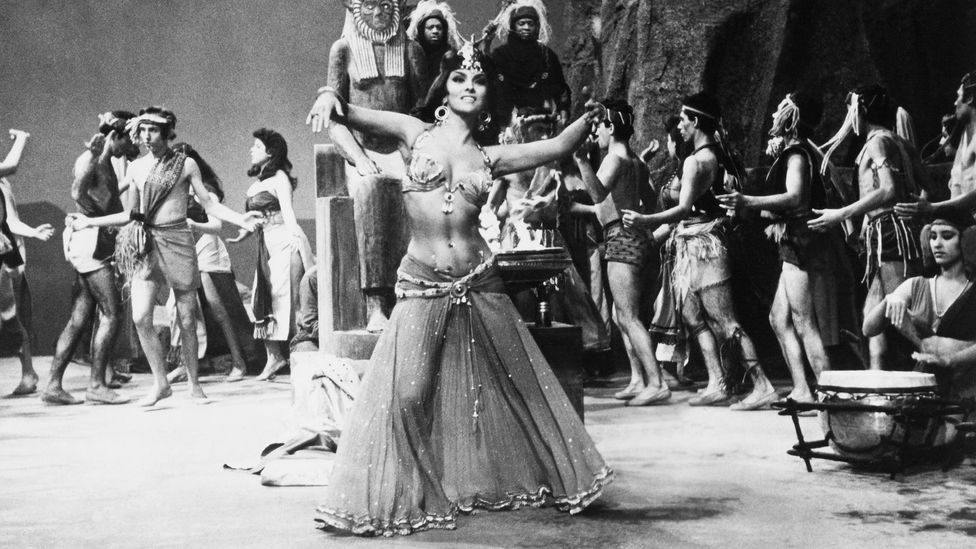

Information technology'southward a circuitous story – of European racism as well as how useful black biblical figures were to those who wanted to teach religion through art – that helps to explicate the absence of black figures in art history. For Michael Ohajuru on his art tours, that's why information technology's all the more important to try and locate the few representations of the black Queen of Sheba and the black Andromeda – and to observe out why they disappeared. The huge influence that Western fine art history has had on our imaginations when it comes to visualising figures from the Bible or classics is arguably one that needs constant interrogation. Under such a lens, Gina Lollobrigida playing the Queen of Sheba in the 1950s or Alexa Devalos playing Andromeda go problematic.

Italian actress Gina Lollobrigida played the role of the Queen of Sheba in the 1959 motion picture Solomon and Sheba (Credit: Getty Images)

"I think for the purpose of showing people and kids that there are these pictures, that's really important," McGrath says. "What was really happening with these artists and what prompted them to do these pictures, well, it's a bit complicated."

If y'all would like to comment on this story or anything else y'all accept seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook folio or message united states of america on Twitter .

And if you lot liked this story, sign upward for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter , called "If You Only Read 6 Things This Week". A handpicked option of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Capital and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20190114-how-black-women-were-whitewashed-by-art

0 Response to "Black and White Pictures of People Scratch Art Woman"

Post a Comment